Renker, Elizabeth. “Resistance and Change: The Rise of American Literature Studies.” American Literature 64.2 (1992): 347-365. JSTOR. Web. 13 September 2016.

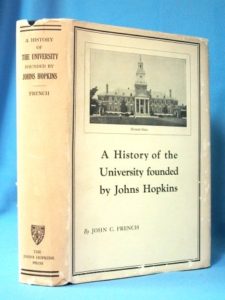

Renker’s essay focuses on the rise of American literature as a discipline in American universities, particularly at Johns Hopkins. Since Hopkins believed firmly in the sciences, the school powers were not apt to incorporate literary fields, especially fields that were perceived as effeminate, like American literature (347). Eventually, due to the diligence and power of one faculty member at Hopkins who became the first to offer and teach American literature at the university, John Calvin French, students were able to study this discipline from 1906 until French’s departure in 1927 (351). Once French left, American literature courses were once again removed from the catalog; however, American literature courses ultimately became more prominent due to elevated interest and patriotism after WWI and WWII. Even though Renker meticulously concentrates on American literature’s rise at Hopkins, she also discusses the lack of attention American literature received at other universities and among scholars in general.

According to Renker, American literature began to receive minimal attention in American colleges during the 1870s, and very few institutions of higher learning offered studies in American literature before the end of the 19th century (352). As noted by Bruce McComiskey in English Studies: An Introduction to the Discipline, when referencing Gerald Graft’s statement that there were no academic literary studies in America until the last portion of the 19th century, the modern university’s inception is actually what introduces English studies into the mainstream (McComiskey 6-7). Essentially, most private schools felt that American literature was inconsequential, public schools were more focused on sciences, and other schools just felt that the subject should be for women (352). Nevertheless, even in the late 1800s and early 1900s, high schools were “spending a substantial amount of time on the subject” (Renker 356). Just like in American high school’s today, the importance of America’s culture and history was prevalent in the works of American literature; therefore, public high schools could direct their readings and teachings toward all enrolled students, whether those students would eventually attend college or not.

Meanwhile, one way that the defeminization of literature occurred was due to the impact of philology. PHILOLOGY, which was defined by one Hopkins professor as, “the application of scientific method to the study of literature,” helped give the profession of modern languages dignity and importance (348). Bruce McComiskey also focuses on philology’s influence in America, for philology incorporates historical and cultural contexts into its study (McComiskey 8). Although philology did not mesh well with American literature, it did help transition some scholars to a new way of thinking about texts. Philology’s impact on American literary studies is debatable, and while it may have assisted in bringing American literature to light, “it was not deployed in the service of American literature, [American literature contained] too recent and too thin a body of texts to lend itself to philological investigation (350). While this may seem ludicrous to suggest, since there were plenty of American texts available in the late 1800s, the fact remains that scholars, students, and professors were not as familiar and did not find value in works of American literature at that point in history.

Additional Sources:

McComiskey, Bruce, ed. English Studies: An Introduction to the Discipline(s). Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2006. Print.

*To view the full text version of Renker’s essay, click the link below (ODU login will be necessary):

http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.odu.edu/stable/pdf/2927840.pdf