As Henry David Thoreau wrote in Walden, “Authors, more than kings, exert influence on mankind” (73). When Thoreau published these words, he was not pontificating about his own prowess as a writer; instead, he was attempting to articulate the importance and impact of all writers, books, and written language. Certainly, Thoreau, along with other American transcendental philosophers, had experienced the magnificent power of learning via literature; in fact, the knowledge he gained through reading must have kindled some of the ideas he would eventually publish for others to imbibe. With this assertion in mind, and using the method of TEXTUAL ANALYSIS, I propose to perform an INTERTEXTUALITY study between American transcendental literature and philosophical literature from earlier time periods and varying cultures. Although Emerson and Thoreau, the two authors who fashioned my paramount objects of study, gave the impression that they were speaking as individuals, intertextual analysis realizes that texts are created “out of the sea of former texts” (Bazerman 83). While Bazerman’s overview of intertextuality focuses on the explicit and implicit relations that texts possess, the varying levels of intertextuality also come into play, many of which play into the roles of transcendental writing: drawing explicit social dramas, using statements as background, support, and contrast, and relying on preconceived beliefs and ideas (87).

Since societal problems, philosophies, and beliefs have been promulgated for centuries, I feel that there are myriad connections between transcendental works and literature published prior. I have no doubts that many of the transcendentalists’ ideas were novel; however, it is also evident that writers like Emerson and Thoreau placed old ideas into a new context, thus exhibiting various forms of recontextualization. Previous studies have been conducted regarding the foundation of American transcendental thought, yet most of these investigations link Emerson to English Renaissance writers, Wordsworth, or other romantic writings from Europe. Meanwhile, Thoreau’s basis in transcendental thought resides with Emerson, his mentor. These types of studies are factual and sometimes painstaking, but they also seem to posit significantly recognizable information, for there are plenty of journals and other published accounts where Emerson and Thoreau articulate the origins of some of their fundamental philosophies. Nevertheless, my research will venture to uncover similar concepts in texts written in numerous time periods and places, texts that may or may not have been encountered by Thoreau or Emerson. Instead of focusing on romantic or renaissance writings, the majority of my studies will reflect writings from the English Restoration, English Reformation, Age of Reason, and the Puritans. While some scholars have made subtle connections between American transcendentalism and English Reformation/Puritan writings, I plan to enhance these studies by looking specifically at works by Samuel Johnson and Jonathan Edwards. Moreover, I intend to link some of the ideas posed by the transcendentalists to the notions disseminated by Thomas Paine, a more unique study that will combine reason with romance. As Rebecca Gould writes, transcendentalists felt that knowledge should be divided between the concept of understanding through rational reflections and the process of reason, which transcendentalists feel is an inherent human gift that every person should nurture (1653). This evidence promoting the importance of reason among transcendentalists should assist in connecting Paine’s writings with those of Emerson and Thoreau.

In attempting this enterprise, I already realize that I will encroach into areas that are already hazy, probably making them cloudier on occasion. For example, one of the major debates among scholars of American transcendentalism and textual analysis concentrates on examining American transcendentalism’s identity. This involves where the transcendentalists received their inspiration, but more importantly, the debates focus on reasons behind the movement and a proper labeling of the movement. My loyalties lie with critics like Fulton and Osgood, scholars who adamantly oppose the view that American transcendentalism is just a Lockean revolt (Fulton 392). Likewise, these scholars are apt to believe that the American movement was mostly conceived as a rebirth of the European Renaissance/Restoration (390). Of course, this is one area where I will slightly disagree, since I plan to research origins also associated with the Age of Reason and Puritanism. As for the other side of the debate spectrum, I will not accept Matthiessen’s sweeping notion that the American transcendental movement was its own innovative entity and not a rebirth from other climes (Fulton 384).

Although I disagree with Matthiessen’s claim regarding American transcendentalism, I do agree with his identification of the NEW CRITICISM as a mode of study that combines cultural and historical attributes (Graff 217). On the surface, this might not seem pertinent to my intertextuality study; however, without the New Criticism, transcendental studies may not have experienced its rebirth among critics. While many New Critics sought to separate history from literature, others, like Matthiessen, helped fashion the cultural and historical methods so predominant today. Still, American transcendentalism’s place within the New Criticism is murky and contradictory. Since there appears to be a drastic increase in transcendental studies in the 1930s, this seems to coincide with the spawning of the New Criticism (Paine 631). Nevertheless, it must still be noted that the New Critics showed contempt for any writings that were academic and political, yet this same movement promoted writers like Melville and Thoreau (Graff 213). Hashing out these apparent contradictions will be integral when I conduct my study, and in order to fulfill the final phase of my scholarly study it will be vital to identify Thoreau and Emerson as valid authors relevant to New Criticism’s scope, for this will promote my perspective that recognizes American transcendentalist literature as being worthy of postcolonial analysis.

*Click HERE to take a brief survey regarding your opinions about connections between American transcendentalism and other works/cultures.

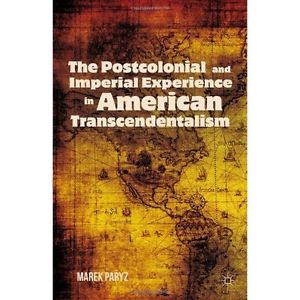

POSTCOLONIAL theory and American transcendental writings are rarely tied to one another, but I see great potential and merit to an examination that links the two. Booker’s definition of postcolonial theory, which is referenced in English Studies: An Introduction to the Discipline(s), is as follows: “Postcolonial theory arises in a cultural context informed by the attempt to build a new hybrid culture that transcends the past but still draws on the vestigial echoes of precolonial culture, the remnants of the colonial culture, and the continuing legacy of traditions of anticolonial resistance” (McComiskey 255). After all, as my intertextuality research will show, transcendentalist writers do indeed draw on past cultures while integrating a framework for a new culture. Furthermore, Renu Jeneja describes postcolonial literatures as works that alter a person’s way of thinking about two different cultures (65). Since this is the case, I see no viable argument against joining these two areas of study, for I agree with the majority of critics who articulate the fact that postcolonial studies should focus on domineered cultures and those individuals who are forced to succumb to society’s whims and colonialism’s influence. Essentially, I see the transcendentalists as a minority, a small group of people who are trying to fight against colonialism’s impact while establishing their own unique hybrid culture. Meanwhile, it must be noted that some connections between transcendentalist works and postcolonialism have been conducted, but these studies tend to reflect feminist theory based around the works of Margaret Fuller, the most prominent female transcendentalist who published feminist literature in The Dial, which was the Transcendentalist Club’s magazine (Miller 120). Instead of this tactic, I will continue to examine Thoreau and Emerson through the postcolonial lens. While performing this study, I will align myself with Marek Paryz, one of the few scholars to publish a study devoted to transcendentalism and postcolonialism. Published in 2012, Paryz’s book analyzes postcolonial aspects found in Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman; in fact, Paryz clearly expresses Thoreau’s postcolonial position through his notions of living in an inescapable empire (100).

While I realize the magnitude of my entire study is immense and challenging, I also realize that it may be even more demanding to package everything together in a cohesive manner. In order to even attempt this rigorous endeavor it will be essential to understand all of my potential objects of study, whether they are works by Emerson, Thoreau, Edwards, Paine, Johnson, or even Paryz. Along with understanding these works, comprehending the theories prevalent during these publications’ time periods and the historical influences associated with the philosophies contained within will need to take precedence. No doubt, this will not be easy, for there will be myriad genres covered in the study: philosophical fiction, classic fiction, memoirs, essays, autobiographies, and narrative nonfiction. Aside from the various theories associated with each genre, accruing professional knowledge through associations will be imperative. For example, joining groups such as the Thoreau Society, the American Philosophical Association, and the Thomas Paine National Historical Association could all prove beneficial, for each of these organizations promote publications and offer valuable professional conferences that are worth attending. Even though I am aware of the prospective challenges this study holds, perhaps my biggest concern involves potential biases that I possess. Overall, I place great credence in the philosophies implemented by the American transcendentalists, but I need to make sure that my biases do not affect the true nature of my study. Most importantly, while researching, I need to remind myself that it doesn’t matter if the ideas articulated by the American transcendentalists were original or not. I don’t need to place Emerson and Thoreau upon a pedestal; instead, I need to find out where their brilliant ideas originated, for the philosophies are most significant, not the men or cultures from where they came.

Works Cited

Bazerman, Charles, and Paul Prior, eds. What Writing Does and How It Does It: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004. Print.

Fulton, Joe B. “Reason for Renaissance: The Rhetoric of Reformation and Rebirth in the Age of Transcendentalism.” The New England Quarterly 80.3 (2007): 383-407. JSTOR. Web. 21 October 2016.

Gould, Rebecca Kneale. “Transcendentalism.” Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. ed. Bron Taylor. New York: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, 2010, Print.

Graff, Gerald. “The Promise of American Literature Studies.” Professing Literature: An Institutional History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987, pp. 209-25. Print.

Juneja, Renu. “Pedagogy of Difference.” College Teaching 41.2 (1993): 64-70. EBSCOhost: Education Research Complete. Web. 18 October 2016.

McComiskey, Bruce, ed. English Studies: An Introduction to the Discipline(s). Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2006. Print.

Miller, Thomas P. The Evolution of College English: Literacy Studies from the Puritans to the Postmoderns. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011. Print.

Paine, Gregory. “Trends in American Literary Scholarship with Reviews of Some Recent Books.” Studies in Philology 29.4 (1932): 630-43. JSTOR. Web. 28 October 2016.

Paryz, Marek. The Postcolonial and Imperial Experience in American Transcendentalism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Ebook Library. Web. 24 October 2016.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden, Civil Disobedience, and Other Writings. ed. William Rossi. New York: Norton, 2008. Print.